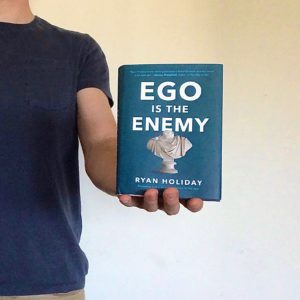

Everyone has an ego. If you don’t think you do, that’s your ego telling you that you don’t. It’s the voice inside that processes the world and tells you everything you want to hear. Ignore it at your own peril. “Perhaps you’ve always thought of yourself as a pretty balanced person. But for people with ambitions, talents, drives, and potential to fulfill, ego comes with the territory.” This quote is taken from page one, as Holiday introduces us to his framing of the ego. He continues: “Precisely what makes us so promising as thinkers, doers, creatives, and entrepreneurs, what drives us to the top of those fields, makes us vulnerable to this darker side of the psyche.” It needs to be kept in constant check.

Everyone has an ego. If you don’t think you do, that’s your ego telling you that you don’t. It’s the voice inside that processes the world and tells you everything you want to hear. Ignore it at your own peril. “Perhaps you’ve always thought of yourself as a pretty balanced person. But for people with ambitions, talents, drives, and potential to fulfill, ego comes with the territory.” This quote is taken from page one, as Holiday introduces us to his framing of the ego. He continues: “Precisely what makes us so promising as thinkers, doers, creatives, and entrepreneurs, what drives us to the top of those fields, makes us vulnerable to this darker side of the psyche.” It needs to be kept in constant check.

This book is not the type of book that is best read cover to cover, but rather one to pick up whenever you need a hit of inspiration. It’s like a mini-bible, specifically about the ego, aimed at shedding light on the ego’s tactics. Maintaining a healthy relationship to our own ego requires continual effort, and the longer we ignore it, the more it collects dust. Picking up this book when you need it is equivalent to cleaning that dust from the corners of your mind. If you own anything that you value, then you understand the importance of keeping your things clean and in good working condition. The mind, and within this context the ego, is no different.

One of the most important ways to keep the ego in check is education. More specifically, acknowledging when there is something you don’t know and taking the steps required to learn it. This is the act of putting the ego and ambition into someone else’s hands. The best time to learn is in the aftermath of failure, for every great failure comes packaged together with the opportunity to learn from it.

In 1963, after her husband committed suicide, Katherine Graham was left alone at the helm of The Washington Post. She had led a comfortable, well-off life up until that point, when she was unceremoniously thrown into the lions den of the competitive business world (not only was she a novice, but she was also a woman in a male-dominated industry in the 1960’s.) She readily acknowledged her lack of ability and ignorance of common business practices and knew the road ahead would be a tough one. While outsiders were convinced the company would fold, she proved them all wrong, publishing the now infamous Pentagon Papers, forming a lasting friendship with Warren Buffet, and bringing the stock price of the company from $1 a share in 1971 to an astounding $89 a share in 1993. Did she screw up along the way? Of course she did. But despite her naïvety, she remained conscious of her ego as she took over as president and publisher of the company. Graham saw every misstep as an opportunity to learn and improve, which she did in leaps and bounds. Her humility towards knowledge was her greatest strength.

I was recently a victim to my own ego and the recovery has been arduous. Last fall I dated a woman (we’ll call her Rebecca) for about six weeks, from the end of September to the beginning of November, and really liked her a lot. She liked me too, but not to the same extent that I liked her. I saw the red flags at the time, like her ignoring my texts and calls while I was always quick to respond, but I thought that if I kept being awesome she would come around and decide to date me. Turns out I had the opposite effect and I smothered her and she pushed me away further. My ego and my desire to date her blinded me to the reality of our mismatched feelings and I naively continued on, assuming everything would work out the way I wanted. Then, when she broke it off, I was crushed. I thought about her every day for weeks. It was a real gut check, from the first girl I’d met in about two years that I had true genuine interest in.

Similar to how I crashed and burned, egotism has pushed megalomaniac figures like Howard Hughes and John DeLorean to drive their companies into the ground as well (Hughes also literally crashed one of his first prototype airplanes, his ego refusing to let anybody but himself test-fly it.) DeLorean, likewise, drove his company into the ground by flaunting proven business tactics and never taking responsibility for his actions. Their egos only allowed them to hear what they wanted, and everyone else could take a hike. Conversely to these two men, the military genius William Sherman has a name that has mostly been lost to history. Sherman is the Union commander who stormed his troops through the heart of the south and effectively won the war for the north. Yet, Ulysses S. Grant is the name we are taught in schools. William Sherman was repeatedly offered a place in politics, but he declined, having done his soldierly duty, his ego craving nothing more than a peaceful retirement. Similarly, a man named George Marshall was chief of staff of the United States Army during the Second World War. He was so successful as a military strategist and organizer that when the war was over, the plan to rebuild Western Europe was literally named after him (The Marshall Plan, which sent 12 billion dollars in foreign aid abroad to help the decimated countries and communities of post-war Europe.) Yet again, it is names like Eisenhower, Patton, and Roosevelt that are remembered in the history books. When we examine the Howard Hughes’ and William Shermans of the past, we can see how the ego is often on display in extremes. Some men have too much, some not enough. We must find each of these extremes within ourselves. Too much ego, and we’ll never learn from our mistakes and improve. Not enough, and we’ll never receive recognition when we achieve a great and hard-fought goal. It is important to appreciate the delicate balance that must be struck.

For example, I produce hip-hop music, and there is a part of me that desperately wants people to listen to my music, and to love it the way that I love my favorite artist’s music. The part of me that needs that validation is definitely ego-driven, but I think it is a healthy egoism because it drives me to be the best musical artist I can be. Compare that to the way I ignored Rebecca’s signals that she didn’t like me as much as I liked her. That was definitely an unhealthy egoism, because I thought I was going to get the relationship I wanted. So there are different scenarios that one encounters in life that require different levels and/or applications of ego. With my music, my ego pushes me to keep writing and producing and being the best artist I can be. With Rebecca, I let my emotions hop into the drivers seat at the wrong time and they carried me away until I crashed! “Many significant life changes come from moments in which we are thoroughly demolished” Holiday writes, and I couldn’t agree more. That crash was what inspired me to pick up this book.

While the title of this book may present the ego as an enemy, it is one we all must live with, and I personally don’t believe ‘enemy’ is a very good term for it. Our egos are our life-long companions, and we must learn to coexist with them the way we would with a significant other. Ask anyone who’s been married longer than five minutes and they will tell you that relationships take work. This applies to all relationships, especially our relationship to our own ego because it is one we can never escape. Of course, escape it is not the goal. Working together in harmony is the goal, and while we will inevitably falter through the successes and failures of a lifetime, our ego can either be the tyrannical one in the driver’s seat or the helpful guide in the passenger seat. The choice is up to you.