At the age of 36, Paul Kalanithi was diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer. He was at the tail end of over a decade of study as a doctor specializing in neurosurgery and just as his career was about to begin, and undoubtedly soar to great heights, he was sidelined with an impossibly grim illness that led to his untimely death only a short 22 months later. During that time, he wrote this book, a reflection on his life, on medicine, and most importantly, on mortality.

At the age of 36, Paul Kalanithi was diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer. He was at the tail end of over a decade of study as a doctor specializing in neurosurgery and just as his career was about to begin, and undoubtedly soar to great heights, he was sidelined with an impossibly grim illness that led to his untimely death only a short 22 months later. During that time, he wrote this book, a reflection on his life, on medicine, and most importantly, on mortality.

Part one is pre-diagnosis and all about his life growing up as a child of Indian immigrants to the United States. His father was a cardiologist and his mother a physiologist and they both exposed Kalanithi and his brothers to science and the medical fields when they were young. In addition to this, his mother insisted on exposing her children to classical literature and Kalanithi details how he grew up reading authors like T.S. Eliot, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Albert Camus, and Virginia Woolf. He developed a love of literature and a keen interest in philosophy as a young man, especially the topic of life and death, and went in search of answers in many places. He eventually pursued majors in both English literature and human biology, reflecting his interest in the human brain from both an intellectual and a physical perspective.

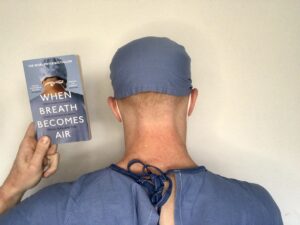

Part two of the book details his heartbreaking cancer diagnosis and his determination to continue to live his life to the fullest despite his bleak future. “Even if I’m dying, until I actually die, I am still living,” he writes. He was in his final year of residency when he was diagnosed and despite trying to finish, his body could not endure the long hours required, and he ultimately had to give up on his dream of neurosurgery. He was forced to say goodbye to his identity as a doctor and instead pick up a pen and embrace a new identity as a writer. He wrote tenaciously and desperately, trying to finish his memoir before his cancer finished him.

His writing is soft and powerful and reading his book was like listening to the voice of a trained physician, someone who had practiced having hard conversations with families in distress. “The physician’s duty is not to stave off death or return patients to their old lives,” he writes, “but to take into our arms a patient and family whose lives have disintegrated and work until they can stand back up and face—and make sense of—their own experience.” In a cruel twist of fate, he had to take his own advice as his role changed from doctor to patient, and it was fascinating to travel through this terrible transition with him.

This book is equal parts uplifting and heartbreaking. It’s filled with the same questions we all ask ourselves: Are we happy? Are we really living the life we want? What would we do if we only had a limited time on this planet? Sadly, Kalanithi was faced with this reality sooner than the rest of us, and yet he answers these questions by continually choosing life. Personally, I found his optimism remarkable. He continued to believe in his future even when all the signs were indicating that he shouldn’t. Despite his diagnosis, he and his wife decided to have a child—perhaps foolishly, perhaps bravely—because they weren’t going to let life dictate to them how they were going to live. Holding his daughter in his arms is one of the highlights of his short life, and this book is a treasure that she will be able to cherish for the rest of hers.

While Kalanithi was given a shorter timeline than the rest of us, we all must determine what is truly important in our lives, and this book is a push in that direction for whomever reads it.