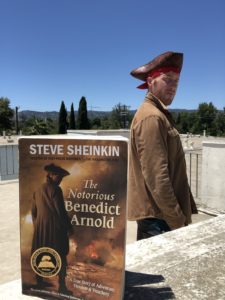

The story of Benedict Arnold is a story about the evils of egoism.

The story of Benedict Arnold is a story about the evils of egoism.

In a day in age when honor and reputation were a man’s most prized possessions, Benedict Arnold was his own worst enemy. Arguably one of the bravest (and most aggressive) generals from the Revolutionary War, Arnold’s service to his budding country started out valiant and courageous. He was leading his countrymen against the British forces in Canada in 1775, before the Declaration of Independence was even signed and a Continental Army formed! “The fact that no one had told Arnold to lead the first foreign invasion in American history meant nothing to him. It was the right strategic move, and he made it.”

While he was a brave commander in the field, always urging his troops forward to victory, he had no gift for politics or the art of promoting his own image and gently persuading others to take his side. “He was brash, bossy, and unable to see other people’s point of view.” His rough personality annoyed his fellow military peers greatly, which led to him being passed over for promotion. This, of course, only enraged him more. Despite his fantastic achievements against the British at Montreal and on lake Champlain (there is a real argument to made that he saved the entire Revolution by stopping the British from storming down the Hudson River from Canada to New York and splitting the northern colonies in two) he received very little public recognition for his valorous service. The stories told by his fellow generals—one prominent one being General Horatio Gates—severely damaged his standing in Congress. “I know some villain has been busy with my fame, and busily slandering me,” Arnold once wrote in a proposed letter of resignation. “I cannot think of drawing my sword until my reputation, which is dearer than life, is cleared up.” These simple words summed up Arnold well: his reputation was dearer to him than his life.

The slights against him were not imaginary. Reporting to Congress on an important battle in Saratoga, one in which Arnold led men and fought valiantly, Gates made no mention of the leading role Arnold and his division played in the day’s success. (The victory at Saratoga was significant because it persuaded the French to side with the Americans in the war.) This was against military tradition and was yet another slight against Arnold’s honor. Not only was his reputation tarnished, but so was his coin purse. Before the war, he had been a successful trading merchant and had volunteered himself and his money to the cause. By this point, however, he was in desperate need of money to help take care of his young sons and sister (his first wife had died years earlier).

After Saratoga, Arnold was confined to a sickbed for months with a left leg that had been shot and smashed horrifically. He would walk with a limp for the rest of his life. Being a man of action, the idle time was not good for his psyche, as he could do nothing but “imagine over and over the beaming faces of congressmen as they handed Gates his medal, as he graciously took credit for the American victory at Saratoga.”

In a strange move, George Washington appointed him the military governor of Philadelphia, a position that Arnold (with his complete lack of political grace) was not appropriate for. He began offending the people almost immediately, putting on large displays of luxury in a city that was suffering from the exploits of war. He hired cooks, maids, and coachmen, and rode around town in a brand new carriage. While he felt as though he had earned these novelties for his services in the war, the people of the city did not.

While stationed in Philadelphia, Arnold met a young woman named Peggy Shippen, who’s family was loyal to the British crown. During the previous year, when Philadelphia had been occupied by the redcoats, Peggy had become close to a Major in the British army named John André, and this connection proved to be Arnold’s undoing. André had recently become the British head of secret intelligence, and through Peggy, began a correspondence with Arnold who expressed his wish to defect to the British side of the war. The slights from his countrymen had finally taken their tole, and he felt that he could best uphold his honor by winning the war for the British, for which he anticipated he would be highly compensated.

Arnold and André’s plan was to surprise attack the American fort at West Point, which was a strategically located base right on the Hudson River. Through a series of chance events, John André was captured carrying the incriminating documents highlighting the plan of attack and was tried and hanged as a spy. Arnold himself barely escaped capture, nearly being caught in his tracks by the one and only George Washington. The plot to was foiled by mere luck.

After that, the rest of Arnold’s life played out with considerably less drama. He led a few small raids for the British against his old countrymen, but as we all know they ultimately lost the war. He moved to England and was unsuccessful in business. He even moved to Canada for a few years and was equally as unsuccessful. He died broken, poor, and unnoticed, the exact opposite of the glory and riches he had once sought after and fought for. Aside from Washington, he did more to win the Revolutionary War than anyone, and had he never given in to his egotistical need for honor and recognition, he perhaps could have been one of the greatest American war heroes in history. Instead, history remembers him as one of its greatest traitors.