In the aftermath of the Second World War, the Soviet Union and the United States were left as the two sole superpowers on the world’s stage. While they had worked together in order to defeat Hitler and the Nazi’s, once their common enemy was beaten, they set their sights on each other. Their governments believed in differing ideologies, and this became the basis for the ensuing Cold War, which lasted from roughly 1945-1990.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the Soviet Union and the United States were left as the two sole superpowers on the world’s stage. While they had worked together in order to defeat Hitler and the Nazi’s, once their common enemy was beaten, they set their sights on each other. Their governments believed in differing ideologies, and this became the basis for the ensuing Cold War, which lasted from roughly 1945-1990.

The Soviet Union was a Communist authoritarian country and the United States was a Capitalist democratic country, and these two competing ideologies fought the Cold War via a nuclear arms race, proxy wars, and vicious propaganda. They are responsible for everything from the Cuban Missile Crisis, to the wars in Korea, Vietnam, and Africa, to the race to the moon. Eventually, the late 1980’s brought about the fall of the Berlin Wall and subsequently the fall of the Soviet Union, and the United States found itself victorious, suddenly and brazenly standing atop the world order. Its democratic ideology—embracing market capitalism and social liberalism—reigned supreme. And indeed, in the immediate aftermath of the Cold War, replica democracies sprang up in numerous countries around the world.

With their victory, the aftermath of the Cold War saw the United States exerting it’s global influence, instructing smaller countries in democratic practices and expanding the number of countries signed onto the NATO pact (an agreement by mostly European nations towards their mutual defense in response to an attack by any external member). While Russia was not a member of NATO, many of the smaller Eastern European states, ones that were formally cast within the Soviet Union, joined the alliance. The more countries that embraced democracy and NATO, the more wary the Russians became. A generation of political propaganda had left both nations highly skeptical of each other: The Russians believed that the United States was an imperialist power committed to spreading capitalist ideology with the intention of dominating the world. Likewise, the United States saw the Russians expanding their ‘evil’ empire of Communism and believed them to be after global control.

While ostensibly spreading capitalism and democracy, what the United States really brought to these fledgling democracies was money. And what happens when you give money to a country that has no political oversight? Mass corruption. Political corruption is directly connected to political finance, and this is exactly what happened: the rich got richer while the poor continued to suffer. “The people lost confidence in the entire system of the post-Cold War world: democracy and capitalism, globalization and the American-led order, which now appeared as corrupted as an old neighborhood being wrecked for a dubious real estate deal or a politician admitting to lies in a secret recording, a soulless exercise that created wealth for the wealthy with no anchor in morality.” Obviously, this trend could not continue forever, and thus authoritarian figures began to rise in popularity as they tapped into people’s outrage at the system.

Enter Vladimir Putin.

“Think about it from a Russian perspective. You see your own billionaires and know they get rich because of their ties to Putin. Public resources like oil and gas handed off to a well-connected few. Criminal wealth laundered into real estate interests, shell companies, and dummy corporations. Then you look at America and what do you see? You see American banks that took reckless risks getting bailed out and you see billionaires profiting at every turn. The owners of oil and gas interests pouring money into politics. The wealthy able to avoid taxation by spreading their money around, moving it off-shore, and creating their own shell companies. All over the world, it’s the same rules.”

When the Berlin Wall came down, many western democracies believed that democratic values and norms were here to stay. Instead, the Iraq War “cracked open the façade that elites in the United States knew what they were doing. They had done something so stupid and self-defeating that it called into question why Americans were the stewards of world order in the first place.” The 2008 financial crises only added more fuel to this already raging fire. The United States had flooded the world with money, much of it tied up in its own financial market. Then the market crashed, and all that money disappeared. Who got bailed out? Banks, corporations, and high-ranking government officials. Who suffered? Everyone else. This exact same theme has been playing out beat for beat over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic response.

So, when a politician like Donald Trump comes along and says he intends to “drain the swamp,” in reference to the corrupt politicians in Washington D.C., it is no surprise that he is met with a positive reaction from the people.

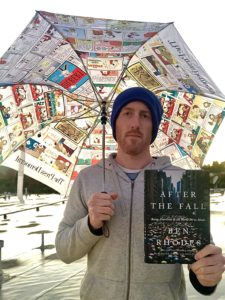

The second half of the book reveals the rise of China. Rhodes describes the Chinese Communist Party as “American capitalism and culture devoid of liberal values and democratic politics.” Xi Jinping has not only shored up political power within China, he has made China a major player on the world’s stage, spreading Chinese influence and money with international projects like the Belt and Road Initiative. Rhodes notes how the balance of power has shifted away from the United States: “It is now America that is becoming more like China—a place of growing economic inequality, grievance-based nationalism, vast data collection, and creeping authoritarianism.”

It’s not just abroad, we in the United States have kneecapped ourselves just as badly as we have foreign nations. For example, the Clinton-era repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, which had regulated commercial banking separately from investment banking, was fueled by $300 million worth of lobbying. Since this decision, we have seen more corporate mergers, more risky bets, and more wealth concentrated among those who could reap the benefits than ever before. For another example, the Patriot Act was signed into law after the September 11th attacks under the guise of antiterrorism. These measures, however, have “set in motion sweeping powers—to conduct surveillance, to restrict immigration, to detain people without trial, to torture people in the custody of the American government, to kill people in other countries.” This is also an example of how propaganda can be used against your own citizens: To name the act the Patriot Act, especially in a time of national unity after the tragedy of September 11th, almost assured its passage into law. Anybody who opposed was framed as being opposed to national patriotism.

Regardless of whether you live in a democracy or under an authoritarian, the reality of how they actually function today is not that different. The people at the top of the political and economic pyramids make the decisions and control all the money and power. The rest of us are subject to their rule.

This bring us to the thesis for Rhodes’ book: that the world is moving towards a singular history, globalization connecting us all whether we are ready or willing or not. Just as the financial and political elite have began to operate via the same playbook, those of us on the bottom rungs of society must also unite globally. The fight for economic and political justice now extends from Hong Kong to Hungary. The secret ingredient to success is bonding together, offering each other the communal support that only the bonds of oppression can know, and advocating for basic human rights.

This is the world that the United States, intentionally or not, has created. And this is the world that we must accept our role in. Not as the leader, but as an active member.