There is no singular, sure-fire way to measure or determine the intelligence of a human being. For many years in the western world we have used IQ tests, but the reality is that analytical intelligence is only one kind of intelligence. There is also creative intelligence, for example, which “examines our abilities to invent, imagine, and suppose.” There is practical intelligence, which Robson defines as “the ability to plan and execute an idea, and to overcome life’s messy, ill-defined problems in the most pragmatic way possible.” There is emotional intelligence (EQ), social intelligence (SQ), and plenty more divisions and subdivisions depending on which clinical psychologist you subscribe to.

There is no singular, sure-fire way to measure or determine the intelligence of a human being. For many years in the western world we have used IQ tests, but the reality is that analytical intelligence is only one kind of intelligence. There is also creative intelligence, for example, which “examines our abilities to invent, imagine, and suppose.” There is practical intelligence, which Robson defines as “the ability to plan and execute an idea, and to overcome life’s messy, ill-defined problems in the most pragmatic way possible.” There is emotional intelligence (EQ), social intelligence (SQ), and plenty more divisions and subdivisions depending on which clinical psychologist you subscribe to.

Where intelligence becomes a trap, and one of the most important pieces of information that Robson brings to light in his book, is when an individual’s intelligence leads them to intellectual certainty. People who are masters of their craft are convinced of the correct way to do a certain task, and they are most often correct. If you are a carpenter, for example, you probably know the best way to sand, stain, and polish a handcrafted table, and that would be fine. Where this becomes dangerous, however, is in the realm of social ideas. The longer you hold what you believe to be an objective truth as true in your mind, the more attached to it you will become. If you’re a carpenter, the stakes are low, but if you’re trying to determine the best way to organize a society of differing cultures, the stakes are high. “One problem is flexibility” Robson writes, “where experts rely on previous experience and lose their eye for changing ideas.” As the Zen monk Shunryu Suzuki put it in the 1970s: “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, in the expert’s, there are few.” This is what made Socrates the wisest man of ancient Athens; his acknowledgment of his own ignorance of all things and his perpetual quest to understand other people’s points of view better. This is also why the socratic method is based around asking questions; because questions are the ultimate form of intellectual humility.

One of the most important elements of research done in this book is on curiosity. Recent brain scans have revealed that curiosity triggers dopamine, which is “usually implicated in [the] desire [for] food, drugs, or sex—suggesting that, at a neural level, curiosity really is a form of hunger or lust.” What this means is that curiosity is its own reward, and if applied to something that deeply interests a person, can even go so far as to become an addiction. Curiosity is also one of the most important antidotes to certainty. Its link to mental elasticity and empathy is crucial for remaining wise, especially in the high-stakes realm of macro-ideas. Benjamin Franklin is an example of the perfect embodiment of these ideas, detesting anything resembling dogma and always remaining curious and intellectually humble about ideas. It was this curiosity about all things that led him to his many inventions and discoveries, and which also aided him in his exemplary political career. If not for him, there is a strong possibility that the Founding Fathers may never have signed and ratified the Constitution of the United States.

Curiosity is also important when considering our emotional compass. Our emotions are a vital source for information gathering and processing and staying closely attuned to them is important for growth and understanding, both of the self and of others. In a business meeting, for example, empathizing with colleagues can better help individuals to reach decisions and navigate negotiations. In group settings as well, having a higher social awareness (both empathetically and empirically) can help with overall group cohesion.

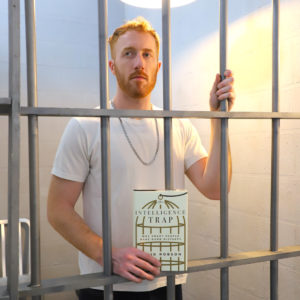

While the thesis of this book is about the blind spots that come with intelligence (like our tendency to see others’ flaws while being oblivious to our own), I found it to actually be more about the ways in which people can achieve wisdom. We have touched on intellectual humility, curiosity, and one’s emotional compass in my review, but there are many more ideas within these pages that deserve attention. Having a growth mind-set, for example, which is the “belief that talents can be developed and trained” over time, as opposed to a fixed mind-set where an individual believes they’ve got what they’ve got and thats it. Or the idea of a pre-mortem, where an individual or a team considers the best-and-worst-case scenarios of a decision before making it. And of course, on the flip side, the dangers of motivated reasoning, which Robson observes as the “tendency to apply our brainpower only when the conclusions will suit our predetermined goal.” How many people (journalists come to mind) operate under this principle, where they decide what angle they want to take on a topic first, and then find supporting evidence second? Is that really a wise way to study and shed light on a pressing topic or public individual?

So, when is intelligence a trap? When you believe in your own intellectual superiority. Robson calls this earned dogmatism, and it is a sure-fire way close yourself off from other people in intellectual, emotional, and social ways. Regardless of your field of employment or study, we should all be mindful of our prejudices surrounding our preferred areas of expertise. We should always do our best to remain open-minded and curious if we have a desire for wisdom.

Leave a Reply