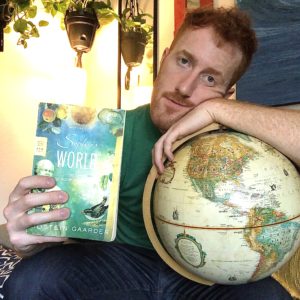

This book is a fun, fantastical hybrid of fiction and non-fiction reading, primarily geared towards younger adults. The fiction part of it centers around a 14-year-old Norwegian girl named Sophie and her philosophy teacher Alberto. The non-fiction elements (Alberto’s lessons to his younger pupil, a proxy for the reader) are a lovely journey through the history of philosophy.

This book is a fun, fantastical hybrid of fiction and non-fiction reading, primarily geared towards younger adults. The fiction part of it centers around a 14-year-old Norwegian girl named Sophie and her philosophy teacher Alberto. The non-fiction elements (Alberto’s lessons to his younger pupil, a proxy for the reader) are a lovely journey through the history of philosophy.

Before reading this book, I had only a layman’s understanding of philosophy. Now, I have a general framework for the evolution of ideas from Socrates to Freud. I can confidently say I understand the difference between rationalism and empiricism, and who came to which conclusion about how human beings process the world around them. (Rationalism is the belief that human reason is the primary source of our knowledge of the world, first developed by Plato. Empiricism posits that the world is primarily derived from what we perceive via our senses, most famously written about by the English philosopher John Locke.) I now also understand why Immanuel Kant’s work was so groundbreaking, because he was the first renowned philosopher to argue that both of these ideas are true and need to be considered together. He subsequently pushed humanity’s collective understanding of the world around us one step further forward, as all great philosophers have done.

I learned that Socrates’ mother was a midwife, which helped him to metaphorically give birth to the Socratic Method. “Socrates saw his task as helping people to ‘give birth’ to the correct insight, since real understanding must come from within. It cannot be imparted by someone else. And only the understanding that comes from within can lead to true insight.” If you’ve ever been in a heated argument with someone, especially about issues of real importance to one or both of you, then you know how futile it is to beg, bribe, or force the other person to accept your reasoning. It does happen occasionally, but more often than not arguments end with both parties leaving with a reenforced belief in their own ideas. The reason the Socratic Method has been around for so long is because it derives its usefulness from asking questions and searching for the truth together. Truth and compromise are collective endeavors. (And by truth in this sense, I don’t mean empirical truths like 2+2=4. I mean theoretical truths. For example, if I said life is short, you might agree, but you certainly couldn’t disagree. Likewise, if I said that life is long, again you might agree, but again you couldn’t disagree.) Theoretical truths are slippery things because they are subjective, which make them prime rib for a hungry philosophical discussion.

The most important lesson in this book is that philosophy is a product of its time. Older philosophers had more theological based ideas in addition to stunted opinions about the roles women played in society. As science gave us answers to the mechanics of the universe, and the Age of Enlightenment spread through Europe and the western world, newer philosophers had less to say about the Gods and more to say about the individual—not to mention more favorable opinions about women. Philosophy mirrors any specified field of study (ie. science, law, or medicine) in that our modern day knowledge stands upon the foundations laid by history. As the collective knowledge of humanity progresses, so must our relationship to the ideas proposed by each new generation. For example, Friedrich Nietzsche (a German philosopher who lived from 1844-1900) was the first philosopher to pronounce that “God is dead.” He was not the first to think it or say it, but he was the first independent thinker to popularize the idea in his writing and it subsequently took a cultural hold in Europe at the time. If he had tried the same thing a few centuries earlier, however, he most likely would have been exiled or executed for heresy. His philosophy was the next step in the evolution of popular thinking. Today, western countries inhabit a culture of abundant secularism. This is the realm from which history will record its next great philosopher(s).

Philosophy as a genre concerns itself with the big existential questions; Why are we here? What is the purpose of life? What can we know for certain about our existence? “There are two kinds of philosophers.” Gaarder writes, “One is a person who seeks his own answers to philosophical questions. The other is someone who is an expert on the history of philosophy but does not necessarily construct his own philosophy.” If you’ve gotten to this point in my review, you clearly have an interest in the subject. So, I ask you, which kind of philosopher are you?

Leave a Reply